Fr: kalmia à feuilles étroites, crevard de moutons, faux-thé

IA: uishatshipaku, uishatshipakua, pinemishi

Ericaceae - Heath Family

Note: Numbers given in square brackets in the text refer to the images presented above; image numbers are displayed to the lower left of each image.

General: A low, multi-stemmed, evergreen, ericaceous shrub, to 1.5 m tall; spreading by rhizomes, especially after fire, and often forming extensive Kalmia barrens [1–4]; it is also a common shrub along headlands. Sheep laurel is poisonous to sheep, goats, cattle, and horses, but caribou and grouse are known to eat the leaves; in Newfoundland, it is not browsed by moose (Van Deelen 1991). The poisonous compound, andromedotoxin (also known as grayanotoxin), is found in the leaves and stems of sheep laurel, but it is also found in other members of the Ericaceae (Ebinger 1974). While the local common name, goowiddy, refers specifically to sheep laurel, its application is often expanded to include all ericaceous shrubs of the barrens.

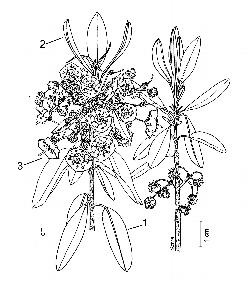

Key Features: (numbers 1–3 refer to the illustration [5]

- Leaves usually in whorls of 3, blades elliptic to oblong, lower surface glabrous, margins entire and slightly revolute.

- New vegetative growth is terminal, above the flowers; leaves are initially erect, but become pendant at maturity.

- Flowers have bright pink bowl-shaped corollas, 10 stamens, with anthers held in small pouch-like depressions until tripped by a pollinator.

Stems/twigs: Young stems are green and finely glandular-pubescent with stipitate glands; winter twigs and branches are light brown to reddish-brown, terete, and glabrous. Lateral buds are small, with 2 exposed scales (Ebinger 1974). Leaf scars are small, semicircular, slightly raised, and have 1 bundle trace scar.

Leaves: The leaves are evergreen, usually occur in whorls of 3, and are simple, pinnately veined, and petiolate. Petioles are up to 1 cm long; new shoots and leaves are finely pubescent (puberulent), but become glabrous with age (glabrate). The leaf blade is firm (coriaceous), flat, elliptic to oblong, 2–5 cm long by 0.5–2 cm wide, often lustrous above, paler and glaucous beneath [6–7]. Leaf bases are tapering (cuneate) to rounded, apices are blunt (obtuse) to rounded, and occasionally apiculate at the tip; margins are entire and slightly revolute [8]. New growth occurs above the flower, with the leaves initially erect, but soon spreading and becoming nearly pendant at maturity [9].

Flowers: Bisexual; in lateral clusters (corymbiform racemes) of several flowers, borne around the stem, in the axils of the previous year's leaves [10–12]. Flowers are borne on slender pedicels, 0.5–2 cm long, which are finely glandular-pubescent. The calyx is green to reddish-brown, 3–6 mm wide, with 5 short lanceolate lobes that are finely pubescent (puberulent) and densely stipitate-glandular [13]. Flower buds are obconical and 5-angled, with 10 small bumps that correspond with the position of the anthers inside the bud [13–14]. Flowers have a 5-lobed corolla, 10 stamens, and a pubescent superior ovary with 5 carpels, an erect style, and a small capitate stigma. The corolla is mainly bright pink (rarely white), bowl-shaped (crateriform), and 6–13 mm across; it has a shallow base, fairly straight sides, and 5 shallow spreading lobes that end in blunt tips. At the base of the pink corolla, a circle of white with a discontinuous border of red lines occurs around the ovary [15].

Anthers are purplish brown and dehisce by means of rounded apical slits at the top of each half (theca) of the anther. Around the inside of the corolla are 10 small pouch-like depressions in which the anthers are secured in place [15–16]. The stamens are held under tension by the trapped anthers, causing the filaments to bend backward as they elongate prior to anthesis. When a pollinator visits a flower, one or more filaments are tripped and the stamen springs forward towards the centre of the flower, shaking pollen on the insect. Sheep laurel pollen can be dispersed in this manner for a distance of 8 cm. Usually, the stamens are released by the proboscis of the pollinator as it searches for nectar, but occasionally a pollinator's legs can release the stamens (Ebinger 1974). Pollination is by insects (entomophily); sheep laurel is self-compatible, but can be cross pollinated by bumblebees and andrenid bees (Ebinger 1974), and various small bees (Rathcke 1988).

Fruit: Each flower produced a small spherical woody capsule, 2–3.5 mm long by 3–5 mm wide, slightly depressed at the top, and borne on long pedicels that arch downward. Immature capsules are green to reddish-brown and covered with a fine layer of short hairs [17–18], but mature capsules are brown and glabrous [19–20]. The fruit is a septicidal capsule, which splits into 5 segments along the walls (septae) between each of the locules and dehisce basipetally, from the top to the base of the capsule [21]. The capsules mature in early fall, persist through the winter, and remain on the stem throughout the following growing season, situated below the new flowers or young capsules [22]. Seeds are numerous, very tiny, and dispersed by wind (anemochory).

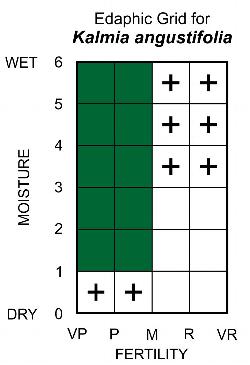

Ecology and Habitat: Sheep laurel is a common shrub throughout Newfoundland; it occurs in forests, barrens, and peatlands; in Labrador, it occurs as far north as the Lower Churchill River valley. Within the forest, it is most abundant on dry to moist, nutrient-poor forest sites, but on richer sites, it may occur sporadically on old dead stumps and logs. Sheep laurel is sufficiently shade-tolerant to persist in low abundance in the understorey of mature forests. However, when forests on nutrient-poor sites are disturbed by windthrow, fire, or cutting, it can expand rapidly through prolific growth of underground rhizomes. If for some reason, tree regeneration is lacking immediately following disturbance, semi-permanent open conifer woodlands or heaths, known locally as Kalmia barrens, may develop (Damman 1964, Meades 1983, 1986). Once established in abundance, the rapid growth of sheep laurel roots and rhizomes creates a deep raw humus layer very resistant to microbial decomposition and, thereby, immobilizes most of the site nitrogen and impedes the growth of other species (Damman 1971).

In central Labrador, sheep laurel commonly grows around the base of black spruce trees on lichen woodlands, particularly those of fire-origin on sand terraces along the Lower Churchill River [23–24]. South of the Lower Churchill area, especially in coast regions, bog laurel very often occupies the niche typically dominated by sheep laurel in central Labrador. Kalmia angustifolia has been documented from lichen woodlands and black spruce-feathermoss (Picea mariana-Pleurozium) stands in southeastern Labrador by D.R. Foster (1983, 1985), but he observed that Kalmia angustifolia decreases "significantly in frequency and abundance following fire" (Foster 1985: 525), which is a very different dynamic than that occurring in central Labrador. In contrast, Foster (1985) documents bog laurel as a sparse understorey species that successfully regenerates following fire in the black spruce-feathermoss forests of southeast Labrador.

Edaphic Grid: See image [25]: the Edaphic Grid for Kalmia angustifolia.

Forest Types: Sheep laurel is most frequent and abundant in the following forest types:

- Betuletum kalmietosum (Kalmia-Birch Forest Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Piceetum cladonietosum (Cladonia-Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Piceetum nemopanthetosum (Nemopanthus-Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Piceetum sphagnetosum (Sphagnum-Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Piceetum taxetosum (Taxus-Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Piceetum typicum (Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

- Piceetum marianae (Black Spruce Forest Association)

- Sphagno-Piceetum-nemopanthetosum (Sphagnum-Nemopanthus-Black Spruce Bog Subassociation)

Within barren habitats, Kalmia angustifolia is ubiquitous, but its abundance and height growth vary considerably depending on relative exposure to wind and protection by snow cover in winter. On the most sheltered barren sites, situated on lower slopes or near the forest edge, its cover can reach 50–75% and 50–100 cm height. This is the habitat of the Kalmia barrens, including the associations: Kalmietum angustifoliae, Kalmio-Myricetum gale, Kalmio-Alnetum crispae, and Kalmio-Sphagnetum nemori (Meades 1983). On the more windswept highlands and coastal headlands, where snow cover is shallow or lacking, Kalmia angustifolia persists as a procumbent shrub intertwined in the dense mat of Empetrum barren. Here, its cover is usually less than 10% and 5–10 cm height. Empetrum barrens include the associations Empetro-Potentilletum tridentatae and Empetro-Racomitrietrum lanuginosae. In alpine barrens (Diapensio-Arctostaphyletum alpinae), Kalmia angustifolia also occurs with a prostrate growth form, with cover less than 5%. Where the barrens experience repeated wild fires or prescribed burns for enhanced blueberry production, Vaccinium angustifolium is the dominant shrub, forming the Vaccinietum angustifolii Association. Kalmia angustifolia may be almost eliminated from these barrens, but can regain dominance within 5–10 years if fire disturbance is relaxed.

Within peatland habitats, Kalmia angustifolia is most abundant in the relatively dry, exposed coastal bogs (Vaccinio-Cladonietum boryii) and the hummocks of ombrotrophic raised bogs (Kalmio-Sphagnetum fusci [26]) (Pollett and Bridgewater, 1973). In these habitats, it has 25–50% cover with heights of about 20–30 cm. It is also frequent, but with reduced cover, in the fen hummock community (Calamagrostieto-Sphagnetum fusci Pollett and Bridgewater, 1973). A comprehensive overview of peatland vegetation in Newfoundland and Labrador can be found in Wells (1996).

Barren and Peatland Types: Sheep laurel is also found in the following vegetation types:

- Calamagrostieto-Sphagnetum fusci (Fen Hummocks Association)

- Diapensio-Arctostaphyletum alpinae (Alpine Barrens Association)

- Empetro-Potentilletum tridentatae (Empetrum Barrens Association)

- Empetro-Racomitrietum lanuginosae (Heathmoss Barrens Association)

- Kalmietum angustifoliae (Kalmia Barrens Association)

- Kalmio-Myricetum gale (Kalmia-Myrica Barrens Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Alnetum crispae (Kalmia-Mountain Alder Barrens Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Sphagnetum fusci (Raised Bog Hummocks Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Sphagnetum nemori (Kalmia-Sphagnum Barrens Association)

- Vaccinietum angustifolii Association (Blueberry Barrens Association)

- Vaccinio-Cladonietum boryii (Exposed Bog Hummocks Subassociation)

Succession: Sheep laurel is a somewhat shade-intolerant shrub that can persist in low abundance, but does not grow well under a closed canopy (Van Deelen 1991). In Newfoundland, sheep laurel occurs most frequently on dry nutrient-poor forest sites. Under these conditions, when the forest canopy is opened by windthrow, fire, or clearcutting, sheep laurel can spread very rapidly and, in the absence of adequate conifer regeneration, will form semi-permanent conifer woodlands or barren vegetation (Damman 1964, Meades 1983). Meades (1986) studied the origin and stability of Kalmia barrens and concluded that the establishment of these barrens on previously forested sites was due primarily to a lack of conifer seed source at the time of disturbance.

In the case of fire, this would occur where there are two successive fires on a site before trees were mature enough to produce adequate cone crops (approximately 25 years). The same conditions could also exist if fire were to consume a large cutover that had not attained sufficient maturity to produce a cone crop.

Also, under the humid climatic conditions of eastern Newfoundland, many upland sites evolved to balsam fir dominance in the absence of natural fire and have very little black spruce. With the increase in anthropogenic fires in the post settlement period, most of this forest landscape had insufficient black spruce stocking to survive after fire and, consequently, a rapid expansion of Kalmia barrens occurred over large areas. In the lichen woodlands of central Labrador [27-30], sheep laurel can be very abundant in the early seral phase following fire, but does not persist in later successional stages, as is does on the Island of Newfoundland. This may be due to the fact that, in addition to extremely dry sandy soils and less precipitation, sheep laurel is near its climatic limit in central Labrador. In lichen woodlands of fire origin in northern Labrador, sheep laurel is replaced by glandular birch (Betula glandulosa) and Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum), which appears to have long-term stability.

Finally, the deterioration of the climate associated with the increased opening of the landscape by fire may have caused a decrease in seed viability similar to that observed in subarctic treelines.

In the case of clear cutting, regeneration failure and the succession to sheep laurel dominance has also been observed where cutting occurs in almost pure black spruce forests of fire origin that have little balsam fir advance growth in the understorey. The development of unfavorable seedbed conditions for black spruce, characterized by deep humus and dry litter layer, appears to be the most limiting factor for successful tree establishment. In large clearcuts seed supply could also be a factor since conifers disperse most of their seeds within 2–3 tree heights from the stand edge. Despite the fact that Kalmia barrens occur on previously forested lands, this vegetation type appears to have considerable long-term stability for several reasons. First, the seedbed conditions created by barrens are unfavorable to conifer establishment. Second, because of the relatively short seed dispersal range of conifers, recruitment is limited to the existing forest edge and any process of relay floristics is curtailed by the rapid establishment of poor seedbed conditions, and, finally, even where there is sparse regeneration, the seedling growth is severely retarded by competition with sheep laurel (Meades 1986).

Sheep laurel has the capacity to monopolize the uptake of nitrogen and other soil nutrients through prolific root growth and the formation of a deep raw humus layer (Damman 1971). Other studies have postulated that the poor growth of tree seedlings may be due to allelopathic interactions with sheep laurel (Mallik 1991, Thompson and Mallik 1989, Yamasaki et al. 2002, Mallik and Roberts 2003). Regardless of the ecological mechanisms involved, silvicultural experiments in Newfoundland and elsewhere have demonstrated the need to control sheep laurel and other ericaceous shrubs when establishing conifer plantations. It is generally concluded that if preventive measures, such as herbiciding or scarification, are taken in early successional stages to control sheep laurel, trees can overcome shrub competition through shading in later stages (Thiffault et al. 2004, 2010).

Distribution: Sheep laurel is a north-temperate species native to eastern North America; of the 2 recognized varieties, only var. angustifolia occurs in our Province. Kalmia angustifolia var. angustifolia extends from Newfoundland and Labrador west to Ontario and southeast through the Maritime provinces into North Carolina, while the southern variety (var. caroliana (Small) Fernald) occurs only in the southeast United States, extending from Virginia south to Georgia and west to Tennessee (Liu et al. 2009).

Similar Species: There are 2 other species of Kalmia in Newfoundland and Labrador, bog laurel (K. polifolia Wangenh.) and alpine azalea (K. procumbens (L.) Gift et al.), but only bog laurel has flowers that are similar, although paler, than the flowers of sheep laurel. Bog laurel is usually restricted to wet habitats, such as peatlands and wet woods, but it can occur in moist areas of peaty barrens. The leaves of bog laurel are opposite and sessile, with narrowly-elliptic, very firm blades that are dark green and glossy above, margins are revolute, and the lower surface is white with densely packed short hairs. Its flowers are produced in terminal clusters.