Fr: bleuet à feuilles étroites, airelle à feuilles étroites, bleuet nain

IA: inniminanakashi, atitshi (green berry), minakashi

Ericaceae - Heath Family

Note: Numbers provided in square brackets in the text refer to the image presented above; image numbers are displayed to the lower left of each image.

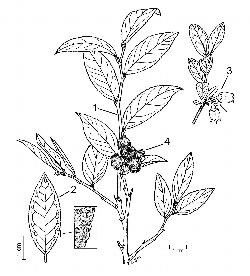

General: An erect low deciduous shrub, 1–6 dm tall, but seldom exceeding 3.5 dm tall; plants have a taproot and rhizomes, often forming large colonies [1–3], especially after fire. Lowbush blueberries are an important local and commercial food crop in Newfoundland and Labrador, eaten fresh or used in baked goods, wine, sauces, and jams. Blueberries are also an important food source for a variety of birds and mammals, often attracting larger mammals, such as bears, to berry grounds. Bears, moose, and rabbits are known to browse on the leaves of lowbush blueberry, while ruffed grouse are known to eat flower buds during winter months (Tirmentein 1991).

Key Features: (numbers refer to the illustration [4])

1. Stems are verrucose and glabrous, except for 2 vertical lines of short hairs.

2. Leaves are alternate, elliptic, with finely serrate margins; each tooth ending in a small stipitate gland.

3. Flowers borne in terminal racemes of several flowers on short shoots at or near the branch tips.

4. Berries are blue with a glaucous bloom, ending in 5 persistent calyx lobes.

Stems/twigs: Young twigs are slightly angled and green to greenish-brown; the surface is finely warty (verrucose) and glabrous [5], except for 2 vertical lines of very fine recurved hairs that extend the length of the stems. Mature stems are reddish-brown to dark brown with flakey bark. Flower buds, located at or near the stem tips [6], are ovoid, blunt (obtuse), and larger than the vegetative buds. Lateral vegetative buds are alternate, small, lanceolate, scaly, and sharply pointed (acuminate) [7]. Leaf scars are very small and narrowly hemispherical, with a single bundle trace scar.

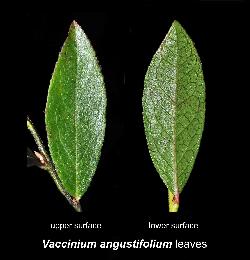

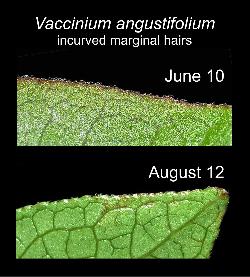

Leaves: Alternate, simple, pinnately-veined, and short petiolate [8]. Leaf blade are narrowly lanceolate to elliptic, 1.5–4.5 cm long by 0.6–1.5 cm wide, bright to dark green above, slightly paler beneath, and glabrous on both surfaces at maturity [9]. Leaf bases are tapering (cuneate), the apex is pointed (acute), and margins are finely toothed (serrulate) with each tooth ending in a small stipitate gland [10]; along the edge of each tooth are a few small incurved white hairs [11–12], which are usually visible only with a hand lens or dissecting scope. Immature leaves are often deep reddish-purple and have white hairs along the leaf midrib, as well as finer incurved hairs along the leaf margins [13], but most of the marginal hairs fall off as the leaf matures. In autumn, leaves turn vivid red [14].

Flowers: Bisexual, in tight terminal inflorescences (racemes) borne on short shoots at or near the branch tips [15–16]; flowers have short pedicels. The green to reddish calyx has 5 low ovate to triangular lobes; the corolla is usually white, often pink when young, 5–7+ mm long, and urn-shaped (urceolate), with 5 short reflexed corolla lobes at the tip [17–18]. The 10 stamens have flat filaments with white hairs along the margins and anthers that end in elongate tubular pores [19 (corolla removed)]; the single pistil has an inferior ovary, a long slender style surrounded at the base by a nectar disk, and a small capitate stigma. Pollination is primarily by bumblebees (melittophily), and cross-pollination is necessary for good fruit set (Javorek et al. 2002, Kevan et al. 1993, Usui et al. 2005). To collect pollen from blueberry flowers, visiting bees must vibrate the flowers in a specific way, causing pollen grains to travel through the tubular extensions of the anthers before being released through the terminal pores. This process, called buzz pollination or sonication, is characteristic of larger solitary bees, e.g., bumble bees (Bombus spp.) and mining bees (Andrena spp.) (Buchmann 1983).

Fruit: In clusters of few to several globose dark blue berries [20–21], 6–15 mm in diameter, with a pale glaucous bloom that rubs off easily [22]. Immature fruits are green to whitish, with red calyx lobes [23–24]. As the berries mature, they turn reddish-purple, then finally blue. The persistent calyx lobes form a short 5-pointed crown at the top of each berry [25]. Lowbush blueberries are edible, have sweet flesh, and about 10–60+ small seeds (Hall et al. 1979). Technically, the fruit is a false berry, since the ovary is inferior and adnate to the hypanthium tube; true berries are derived from superior ovaries, with only the ovary developing into a fleshy berry. Fruits mature in late summer to fall and are dispersed primarily by mammals and birds (endozoochory).

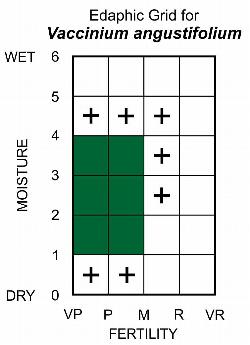

Ecology and Habitat: Lowbush blueberry occurs across a wide range of habitats in Newfoundland, including alpine barrens, lowland heaths, peatlands, and forests; in fact, the only habitats in which lowbush blueberry is lacking are wet nutrient-rich fens and alder swamps. Within the forests, lowbush blueberry is only abundant in the open Kalmia-Black Spruce and Sphagnum-Kalmia woodlands on dry to wet nutrient-poor sites. In the shade of mature forests, lowbush blueberry is only found in small patches, but can rapidly expand in canopy gaps created by blowdown. It only occurs sporadically on raised logs and stumps within richer sites. Lowbush blueberry can expand rapidly in early successional stages following cutting and fires.

Edaphic Grid: See image [26]: the Edaphic Grid for Vaccinium angustifolium.

Forest Types: Lowbush blueberry is usually found in the following forest types:

Abietum gaultherietosum (Gaultheria-Balsam Fir Forest Subassociation)

Abietum taxetosum (Taxus-Balsam Fir Forest Subassociation)

Abietum typicum (Pleurozium-Balsam Fir Forest Subassociation)

Betuletum kalmietosum (Kalmia-White Birch Forest Subassociation)

Betuletum typicum (White Birch-Mountain Alder Forest Subassociation)

Kalmio-Piceetum nemopanthetosum (Nemopanthus-Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

Kalmio-Piceetum taxetosum (Taxus-Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

Kalmio-Piceetum typicum (Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

Piceetum marianae (Black Spruce-Moss Forest Association)

Sphagno-Piceetum (Sphagnum-Black Spruce Bog Association)

Peatland Types:

Lowbush blueberry occurs only on drier peatland types, including exposed coastal bogs, bog hummocks, and strings of minerotrophic ribbed fens in Labrador. It has been described from the following associations (Pollett & Bridgewater 1973, Wells 1996):

Vaccinio-Cladonietum boryi (Coastal Bog-Dry Hummock Association)

Kalmio-Shagnetum fusci (Dry Bog Hummocks Association)

Chamaedaphno-Sphagnetum angustifoli (Ribbed Fen-Low Strings Association)

Barren Types:

Lowbush blueberry occurs with high frequency and with 10–20 % cover in all barren subassociations with acid soils, including Alpine Barrens, Empetrum Barrens, and Kalmia Barrens. In areas that were recently burnt or subject to repeated prescribed burning, it becomes the dominant species, with an abundance reaching 50–75%; these barrens are recognized as a distinct association, the Vaccinietum angustifolii (Blueberry Barrens). Plant height varies considerably with wind exposure, ranging from a prostrate growth form less than 10 cm in Alpine and Empetrum Barrens to an erect shrub 30–40 cm tall in Kalmia and Blueberry Barrens (W.J. Meades 1973, 1983).

In the Limestone Barrens, the lowbush blueberry occurs with low frequency and less than 5% cover, usually associated with Empetrum Barrens and Shrubby cinquefoil-Alpine Rush Barrens, where there is sufficient acidic humus accumulation to mask the underlying basic soils and gravels. It is also a consistent component of the snowbed habitats dominated by cow parsnip. It occurs in the following limestone barren subassociations:

Empetretum-Salicetosum cordifoliae (Empetrum-Northern Willow Limestone Barren Subassociation)

Empetretum-Salicetosum reticulatae (Empetrum-Netvein Willow Limestone Barren Subassociation)

Potentilletum-Juncetosum alpinae (Shrubby Cinquefoil-Alpine Rush Limestone Barren Subassociation)

Heraculetum-Sanguisorbetosum canadense (Cow Parsnip-Bottlebrush Limestone Barren Subassociation)

Succession: Lowbush blueberry can regenerate through seed dispersed by wildlife species and vegetatively from the root collar and through below ground rhizomes (Tirmentein 1991). It increases rapidly following fire and cutting, primarily through vegetative sprouting, and occurs in high abundance for up to five years following disturbance. Lowbush blueberry is not well adapted to shade; thus, on medium to rich sites, competition from raspberries in early succession and in hardwood thickets 5–10 years post disturbance causes vitality and abundance to decline. On dry poor sites lowbush blueberry maintains its cover and production for somewhat longer, but competition from Kalmia and other dwarf shrubs causes a decline in abundance and fruit production. Lowbush blueberry can withstand intense heat, and prescribed burning has been used to maintain blueberry production and enhance wildlife habitat on crown lands in eastern Newfoundland (Peters 1958). On the Avalon Peninsula, the cultural practice of prescribed burning has led to the development of an anthropogenic barren type classified as the Vaccinietum angustifolii (Blueberry Barrens Association) (W.J. Meades 1983).

Distribution: Lowbush blueberry is native to northeastern North America and is found throughout Newfoundland and Labrador, extending north to at least Nain (56° 32' N) (Rouleau and Lamoureux 1992, Scoggan 1978), and west to southeastern Manitoba (Hall et al. 1979). In the United States, lowbush blueberry occurs from Maine to Minnesota and southeast along the Appalachian to North Carolina and Tennessee (USDA, NRCS 2016).

Similar Species: Within the Province, velvetleaf blueberry (Vaccinium myrtilloides Michx.) is known only from Labrador. Where their ranges overlap on the mainland, velvetleaf blueberry and lowbush blueberry often grow together in the same habitat, but velvetleaf blueberry can be recognized by its velvety-soft hairy leaves and downy twigs. Northern blueberry (Vaccinium boreale I.V. Hall and Aalders) is similar to lowbush blueberry, but smaller, less than 1 dm tall. Northern blueberry leaves are also smaller, to 21 mm long by up to 6 mm wide, compared to leaves 15–42 mm long by 6–16 mm wide in lowbush blueberry.

The minute incurved hairs along the margins of the teeth on lowbush blueberry are one of the differentiating features between typical plants of Vaccinium angustifolium and those classified as var. nigrum (Alph. Wood) Dole, which in our opinion, should be treated as a distinct species, black lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium nigrum (Alph. Wood) Britton). Compared side by side in the field, plants of V. nigrum can be differentiated by their more bluish green colour [27]. Other identifying features of V. nigrum include lower leaf surfaces that are glaucous [28], young leaves have leaf margins with a waxy cuticle extending beyond the edge of the serrations, but lack marginal incurved hairs [29], and deep purple to bluish-black berries that lack a glaucous bloom [30]. Although not known yet from Newfoundland and Labrador, it could occur in dry coniferous stands of western Labrador. V. nigrum is typically found in northern Ontario and northern Québec with V. angustifolium in dry coniferous stands with black spruce, larch, jack pine, and an understorey dominated by blueberries, bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng.), wavy hairgrass (Avenella flexuosa (L.) Drejer), roughleaf mountain rice (Oryzopsis asperifolia Michx.), and caribou lichens (Cladina and Cladonia spp.).