Fr: clintonie boréale, lis-boréal

IA: kashkashkatapaku, atapak, anikamin(an)

Liliaceae - Lily Family

Note: Numbers given in square brackets in the text refer to the images presented above; image numbers are displayed to the lower left of each image.

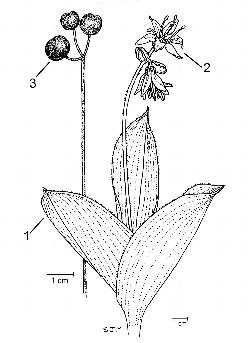

General: A perennial woodland forb, 2–5 dm tall, with yellow, often nodding flowers [1–2]. This common understorey plant of cool boreal forests has slender rhizomes that spread gradually, forming large, long-lived colonies in some areas. The common names bluebead lily and poisonberry both refer to the bright blue fruits, which are inedible and mildly toxic. However, the young leaves are reportedly edible, although acidic in taste (NC State, no date).

Key Features: (numbers 1–3 refer to the illustration [3])

- Leaves basal, simple, with elliptic to obovate, light green blades, 15–30 cm long, tapering at the base and the acute to abruptly acuminate apex; margins are entire and finely hairy.

- The few nodding to erect flowers have 6 greenish-yellow to yellow tepals, 6 stamens, and a single pistil with a superior ovary. Flowers are borne in an umbel-like cluster, terminating a scape.

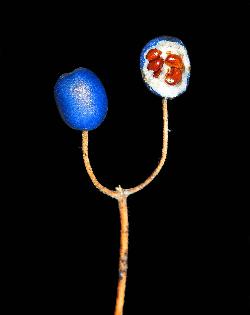

- The fruit is a bright blue, mildly toxic berry with white flesh and several brown seeds.

Stems: Above ground leafy stems are lacking, the flowering stem (scape) is glabrous. Clones are produced from a single parent plant (genet) over many years [4]. Annual shoots die at the end of each season, but the underground stem (rhizome) produces new offspring plants (ramets) in the spring. One study in Maine observed 2 sets of 16 clones over a 3-year period and documented an annual increase of 2% to 20% in the number of ramets produced (Pitelka et al. 1985). Small clones, with 12 or fewer ramets, were determined to be around 20+ years of age, while larger clones were considerably older, but still possessed only 1 to few genets. Also, new plants originating from seed were not observed in these clones (Pitelka et al. 1985). This indicates that vegetative reproduction (production of new ramets) is responsible for nearly all growth in clones of Clintonia borealis.

Leaves: Simple, basal, 2–4, rarely 5; leaf blades are 15–30 cm long by 5–10 cm wide, elliptic, oblanceolate, to obovate, somewhat succulent, keeled on the lower surface, and slightly depressed on the upper surface, above the prominent midrib [5–6]. The blade tapers gradually to the base and the apex, which may be acute or abruptly acuminate; both upper and lower leaf surfaces are glabrous and glossy; margins are entire and finely hairy [7–8]. Leaves turn yellow in autumn [9].

Flowers: Bisexual; 3–8 flowers arranged in an umbel-like cluster terminating a naked scape [10–11]; pedicels are very finely pubescent and equal to or slightly longer than the flower buds [12], but elongate in fruit. Rarely, a smaller, second whorl of flowers or fruits can be found a short distance below the terminal cluster [13]. The erect to nodding campanulate flowers have 6 oblong to lanceolate, yellow to greenish-yellow sepals and petals that look alike (tepals) [14–16]. Tepals are 12–16 mm long by 3.5–4.5 mm wide, and curve backward at the tips as the flower matures; nectaries are present at the base of each tepal. Stamens are 6; filaments are slender, 12–17.5 mm long; anthers are oblong, 2–3.5 mm long, and extrorse, dehiscing along the outer surface to release pollen. The solitary pistil has a superior ovary with 2 seed chambers (locules), a style about as long as the tepals, and a short 3-lobed stigma [17]. Flowers are somewhat self-sterile (Dorken & Husband 1999) and protogynous (Galen et al. 1985), with the stigma receptive before pollen is shed; thus, cross-pollination is necessary for good seed set. The most common pollinators of Clintonia noted in one New Brunswick study were bumblebees [18] (Bombus ternarius, B. terricola, and B. vagans) and solitary bees (Barrett and Helenurm 1987).

Fruit: The 1–6 berries are borne on erect, stiff pedicels and mature from green to bright blue [19–20] or dark blue [21]. Berries are spherical to ovoid, 8–12 mm long, with a shiny glabrous blue surface and white flesh [22]; the top of the berry has a slight dimple or depression where the style was attached to the ovary. Bluebead lily berries have a disagreeable taste and are mildly toxic, so should be avoided. The 8–16 brown seeds are 3–5 mm long. The fruit ripen in August and dispersal is primarily by fruit-eating (frugivorous) birds.

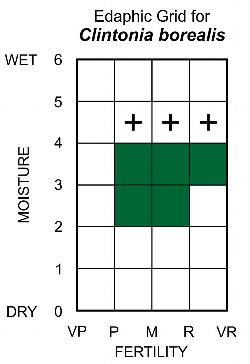

Ecology and Habitat: Bluebead lilies can occur throughout a wide variety of forest habitats, but is most abundant in moist, medium-rich sites with an abundance of feathermoss, particularly, stairstep moss (Hylocomium splendens (Hedw.) Schimp.). Bluebead lily is a shade-tolerant herb that does not respond well to fire or clearcutting, but can survive in the partial shade of gaps created by blowdowns.

Edaphic Grid: See image [23]: the Edaphic Grid for Clintonia borealis.

Forest Types: Bluebead lily is most frequently encountered in the following forest types:

- Abietum clintonietosum (Clintonia-Balsam Fir Forest Subassociation)

- Abietum dryopteretosum (Dryopteris-Balsam Fir Forest Subassociation)

- Abietum gaultherietosum (Gaultheria-Balsam Fir Subassociation)

- Abietum rubetosum (Rubus-Balsam Fir Forest Subassociation)

- Abietum taxetosum (Taxus-Balsam Fir Forest Subassociation)

- Aceretum galietosum (Galium-Mountain Maple Thicket Subassociation)

- Alneto Piceetum (Alder-Black Spruce Swamp Association)

- Betuletum dryopteretosum (Dryopteris-Birch Forest Subassociation)

- Betuletum rubetosum (Rubus-Birch Forest Subassociation)

- Kalmio-Piceetum nemopanthetosum (Nemopanthus-Kalmia-Black Spruce Forest Subassociation)

- Osmundo-Piceetum (Osmunda-Black Spruce Fen Subassociation)

- Sphagno-Piceetum nemopanthetosum (Sphagnum-Nemopanthus-Black Spruce Bog Subassociation)

Foster (1984) records bluebead lily with cover values of 3–10% in his Birch Forest and Fir-Spruce-Feathermoss Forest communities in southeast Labrador. Wilton (1965) includes it in his Fir-Spruce-Birch/Rich Herb type in Labrador.

Succession: Bluebead lily cannot thrive in direct sunlight and, as a consequence, does not survive after disturbance by fire and clearcutting. Recovery after such disturbance is probably very slow compared to other herb species, since establishment from seed is rare and even small clones can take up to 20 years to establish (Pitelka et al. 1985).

Distribution: Bluebead lily is a north temperate to southern boreal species, native to eastern North America. It occurs throughout insular Newfoundland and its range extends north to central Labrador (Scoggan 1978). In the United States, it occurs throughout New England and extends west along the northern Border States to northern Minnesota, and south along the Appalachian Mountains to northernmost Georgia (USDA, NRC 2016).

Similar Species: The leaves of bluebead lily are most similar in size and shape as those of the pink ladyslipper (Cypripedium acaule Aiton), but the latter species has leaves that are dull, stiffly pubescent on both surfaces, and have several prominent parallel veins [24]. In contrast, bluebead lily has somewhat succulent, glossy leaves that are glabrous (except along the margins, which are finely hairy), and a single prominent midrib.

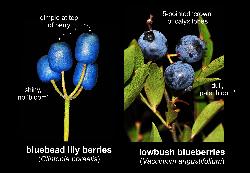

The yellow bell-shaped flowers of bluebead lily are unlikely to be confused with other spring-flowering plants in Newfoundland and Labrador, but the unpalatable, mildly toxic fruits resemble those of blueberries (Vaccinium species). To differentiate between blueberries and bluebead lily berries, look at the top of each berry for 5 small triangular calyx lobes, present only on blueberries. The fruits of blueberries develop from flowers with the calyx (fused sepals) and corolla (fused petals) attached to the top of an inferior ovary. As the fruit develops, the corolla falls off, but the calyx lobes remain on the fruit, forming a small 5-pointed crown at the top of each berry [25]. In comparison, the bright to dark blue fruits of bluebead lily are smooth at the top, with a shallow dimple marking where the style was attached. These fruits develop from flowers with the sepals and petals (tepals) attached below a superior ovary, leaving no marks on the developing fruit after the tepals drop off. Another way to distinguish between true blueberries and the berries of bluebead lily is that most blueberries have a pale glaucous coating (or bloom) that can be removed by rubbing your finger across the berry, while bluebead lily berries are shiny and lack a glaucous bloom [25].

The toxicity of bluebead lily berries is not mentioned in most poisonous plant websites, but several bluebead lily berries may be enough to cause harm. A member of the Newfoundland Wildflower Society, her siblings, and a cousin experienced its toxic effects first hand, when as young children, they mistakenly ate some ‘poisonberries’ collected with their blueberries. While the children recovered, one young boy had to be hospitalized briefly. Since small children are most susceptible to the toxic qualities of bluebead lily berries, care should be taken to check that all the berries have been correctly identified before eating them.